Repair Reflections: PRF’s Sara Quinn has a broken film camera.

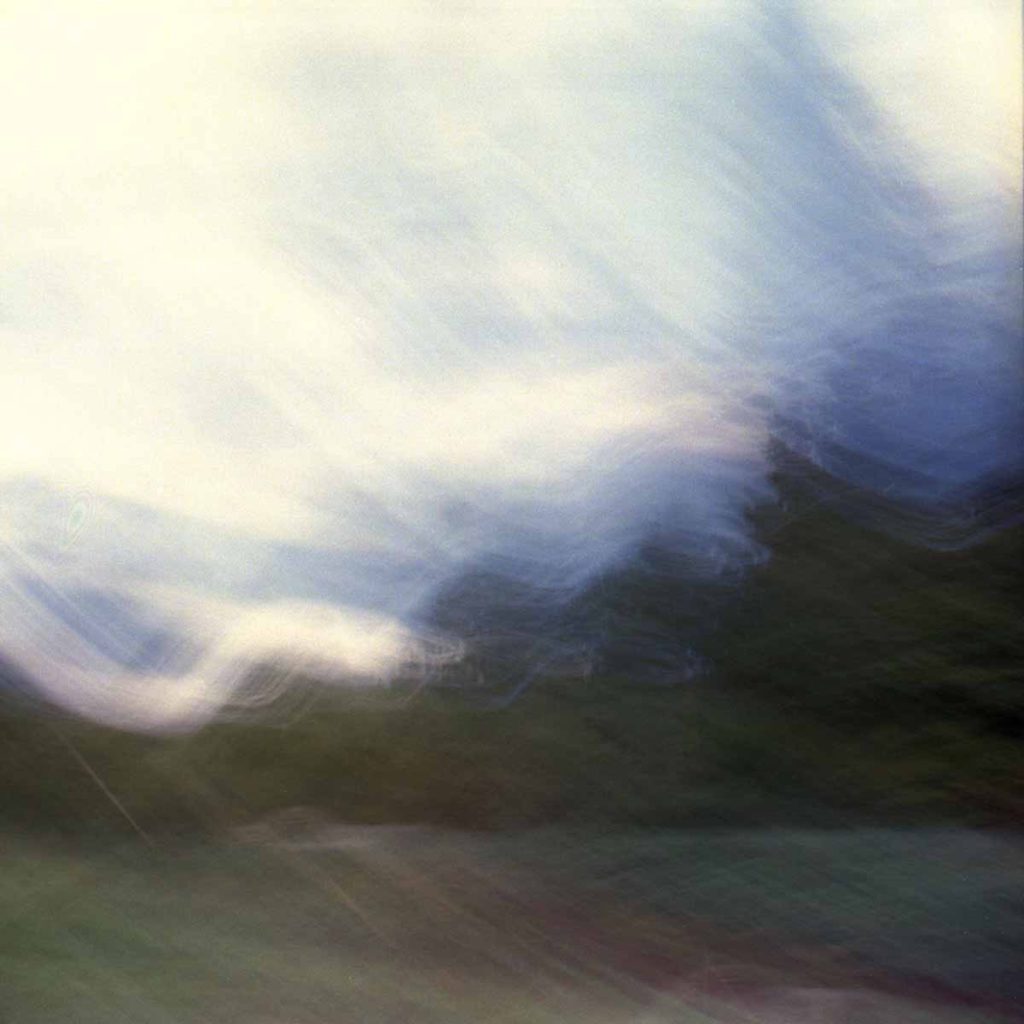

A few years ago, I spent a week visiting my hometown in Northern Idaho. My sister had just had her first daughter. My grandmother was nearing the end of her 96 years. I shot a few rolls of film on my Mamiya 6, a medium format film camera made in the early 90s. The pictures I took were of nostalgia, really: the county fair with its sugary elephant ears and dinky ferris wheel, the tumbling wheat fields of the Palouse, the barn that I’ve been watching stoop lower for as long as I can remember.

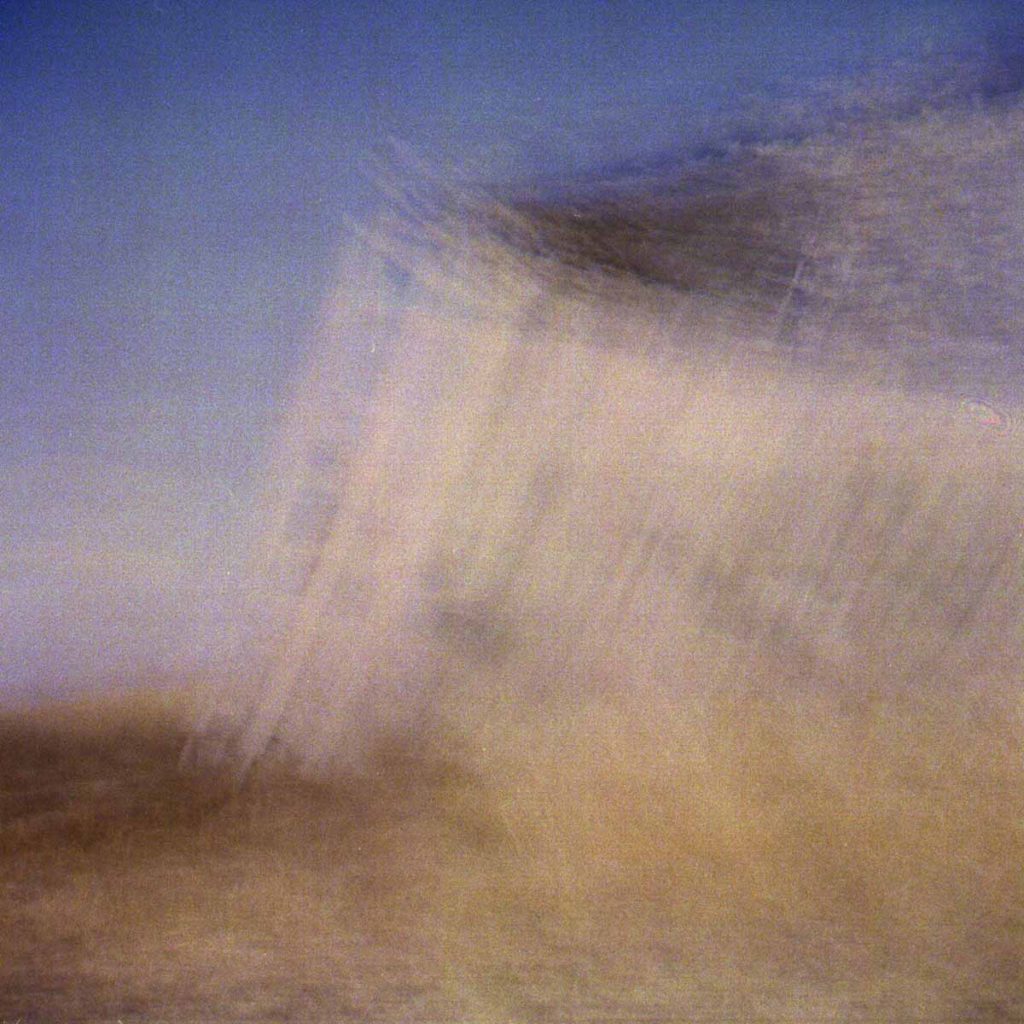

I got back to Portland and developed the film. I remember holding those thin strips up to sky to see the images, too impatient to wait until I got home. Shit, I thought. What happened? Some of the images appeared crisp, well-exposed. But so many were a blur. I biked home and disappointedly scanned them into my computer. Just a batch of failed images.

If you google “light leaks”, you’ll come across all sorts of flaws available for purchase. You can add scratches, dust and grain to your images. It turns out the aesthetic of the broken is marketable. What is it that so intrigues us about the defective?

In this instance, my camera didn’t just have a light leak (though it’s had those, too). Something within the lens element was catching the shutter, causing it to remain open as I wound the film. In doing so, it captured the blurred moments following the picture. I was upset about it at first. I hadn’t been back to Idaho in a while. My grandmother was dying. I probably wouldn’t see my niece until she was crawling, or walking, or who knows when. It felt like those moments had been taken from me.

Visible mending is a repair method that aims to bring new life to torn clothing by adding patches that are often colorful and playful, layering a new story on top of the old memories. While there are many ways to mend your clothes in invisible ways, there’s something about visible mending that excites me. It’s a celebration of the broken, a form of remembering through repair, a subversion of perfection. I wear my jeans all over the place, but I don’t often think about the adventures I’ve had while wearing them. But while on a bike tour along the Gulf of Mexico, I fell and tore those jeans (and my knee). The rip became a story, and the fix a way to keep that story alive. Every time I touch the patch on my knee, and the scar beneath it, I recall not just the moment of falling, but that whole adventure. It brings me back to those weeks on the saddle, sweaty and tired, full of key lime pie and gatorade.

I kept going back to the blurred images. I remember taking my camera apart, trying to figure out the problem, tiny screws in piles on my desk. I remember taking it to the shop – Dot Dotson’s in Eugene – where they dissected the lens and, with sure hands, got it working again. The blurred photos tell a story not just of the moment they were capturing, but of a broken camera. Just like I remember that bike tour by the patch on my jeans, I remember that week in Idaho by the mend.

Just as a colorful patch isn’t appropriate for, say, your business attire, blurred images aren’t always delightful surprises. I like knowing my equipment, knowing what I can and cannot trust, and knowing when a repair is needed. I haven’t had a serious problem with my Mamiya camera in years. But when I do, I’m excited to see what the stories those imperfections can tell.

PRF’s “Repair Reflections” series offers contemplations, ideas, and story to generate thought and conversation around repair-related concepts in our everyday lives.