Marshall is a technician who works on high-end pianos, and focuses on grand piano playing actions— the system of levers that links the keys to the hammers that strike the strings. This niche skillset came slowly over time, through a mix of diligence, hard work and luck, but when Marshall passed the Piano Guild Technician’s test 34 years ago, he expected a simple, straightforward career:

“I thought it was something I would just learn and be able to do it and then ride off in the sunset. Then as a few years go by, you realize it’s years to become a good piano technician. Just to become a good tuner takes hundreds of pianos, and if you want to get good at tuning good pianos, you have to tune good pianos. Because you can get a good piano so much nicer in general, it challenges you to get it nicer. If you get a piano with all these problems, you kind of put in your time to make it better and then you leave. Whereas what I’m doing is trying to make it as good as it can possibly be. And it has the elements to be really really good.”

“The best thing in my career is I was lucky. I have a strong feeling that you can try all you want, but if the chances aren’t there, your life path can go totally differently. I got a job at Steinway, right out of school, for peanuts. It wasn’t money at the time, it was about getting experience. And it was good luck for me because I was working on good pianos, and I was preparing them for sale, so I got to do like 1200 new Steinway preparations out of the crate, over the years.”

Hammers removed from a Steinway piano action, along with a new hammer to be shaped and hung.

Years of work on high-end pianos gave Marshall an opportunity to go into business for himself, and to do more in-depth work on fewer pianos—mostly Steinways and Faziolis. Where many tuners will tune five pianos a day, Marshall spends 3 or 4 hours on a tune, and his work on playing actions can take up to a month. And as his skills improved, he’s been able to focus more and more on the specific tasks he enjoys most.

“I’m still trying to learn, even though I’m dialing back. I wanted to be good at everything, and then I just went ‘Do you even like this? What do you like, if you could do any part? And that’s the action work and the hammer work, and it’s making it sound like a beautiful instrument, not all the stringing and machining, all the hard work. Or the rebuilding of it which can take a whole year.’”

Visits to the Fazioli factory in Italy to observe and train with their factory technicians have raised the standards that Marshall sets for himself: “I thought I was hot because I could do better than the New York Steinway factory. Then I went to Fazioli two or three times, and I was like ‘Oh my goodness, I can get better.’ I wouldn’t say I was getting bored, but I saw how I can make it even nicer.”

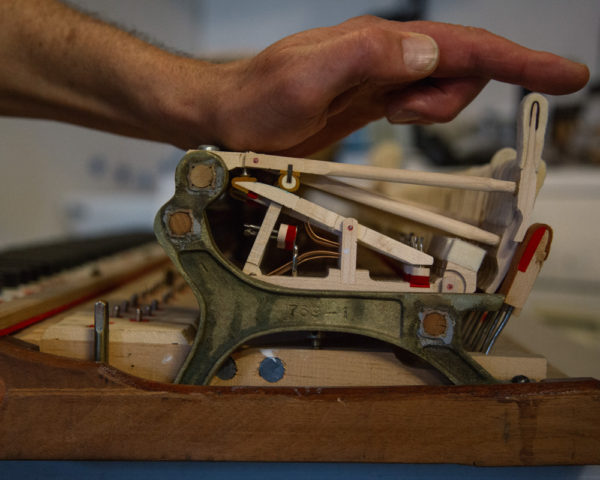

When I visit Marshall he’s in the middle of a custom hammer job. The playing action has been removed from the piano and transported (carefully: “It freaks me out to drive with these. If someone rear-ends me, this is worth way more than my car. It’s worth like three of my Jettas.”) to Marshall’s home shop to fit new hammers and make adjustments, and will then be reinstalled in the piano for final adjustments, tuning, and “voicing”— changing the way the piano sounds and optimizing the sound for its specific location.

A hammer boring jig in the drill precisely positions each hammer for hanging.

The piano in question is a Steinway, about ten years old. It’s getting a new set of hammers. The old ones “weren’t exactly worn out, they just made the piano sound like shit, because of the way they were treated at the factory.” So begins a long, delicate process of shaping the new hammers for weight and tone, then hanging them and making hundreds of adjustments to the action. Adjustments are made for key and hammer height, key weight and dip, and matching the hammers so each strikes all three strings evenly.

“Every note should feel exactly the same, which is affected by all these little adjustments. It’s a process of going through two or three times. Then you tune 230 strings, and usually go twice through on that, because you can only tune a piano that’s in tune. And getting the tuning pins stabilized.”

Then the piano is voiced, by subtly reshaping the hammers, softening them by needling the hammer felt, or hardening them with lacquer. It’s a lot of high skill work, more artistry than technical procedure.

“Technicians often treat themselves like a commodity, and this is not really a commodity. To do this at this level requires way more skill than a guy that’s been doing it for five years. Because there’s a lot going on here, for really valuable instruments and this is really important to the tone, the touch, and how you enjoy it.”

“It can make a good piano great and an okay piano very pleasurable. People aren’t used to an action that almost plays itself, because usually they have to fight it. And when you get to one that doesn’t, it’s very magical.”

Installing and adjusting new hammers in a Steinway playing action. Each hammer and key requires dozens of individual operations and adjustments

Working on pianos is easy to romanticize, but Marshall insists he was still in piano school when he “found out there was no romance anymore, after being in tuning booths for weeks on end with crappy pianos.” Instead, he was hooked by the complexity, nuance, and subtle difficulty:

“This came to me really hard, but I didn’t get bored because of that. I had friends who this came really easily to them, and they got bored with it and didn’t keep pushing themselves. Where I kept saying ‘well, what else can you do?’ I wanted to keep making more for less time so I kept pushing myself to do better jobs.”

Still, there are moments of romance: “When I get to that zone where everything is ringing together and it’s a beautiful tuning, beautiful voicing, and it’s nicer than it’s ever been. I do work where people want me there. It’s not the dentist.”