Repair Reflections: PRF’s Joel Newman doesn’t think the recycle symbol is always helpful.

Sustainability has three R’s: Reduce, reuse, and recycle. No, wait, there’s a 4th: Refuse*. And a fifth: Rot? Or there’s 14!

There’s only space for three on the ubiquitous recycling symbol – plus, three is an inherently satisfying number – but this prompts the question: Why is this the recycling symbol? Why don’t we pay equal attention to the other R’s?

However you count your R’s, recycling ought to be last on the list: It’s an industrial process that requires lots of water, energy and other inputs, and results in lower-grade output material. Industrial-scale recycling has been broken for a while, but the bottom really fell out of the market when China stopped buying recycled material in 2018, in a policy change ominously called “National Sword.” There’s a great episode of 99% Invisible about National Sword that goes in depth on how the global recycling market works and fails to work.

A still from the documentary “Plastic China” shows the informal cottage industry that is recyclable material processing in China.

On the other hand, recycling is easy and it feels good.

Sustainability messaging is always a balancing act: Advocate for widespread adoption of a non-intrusive change with only mild environmental benefit, or set more aspirational environmental goals that require extra effort or lifestyle changes, narrowing the number of people who adopt them.

Hybrid cars are a good example. Are they a positive thing because they save gas, or do they preclude other, more broadly beneficial changes — better public transit, or more bicycling infrastructure, for example — because buying and driving a hybrid feels like an easier part of the solution?

Of course, we at Portland Repair Finder think Repair deserves to be one of the R’s. It’s at the opposite end of the impact vs scale spectrum from recycling; it requires attention and effort, and doesn’t scale easily, but the potential impact is high.

Consider for a moment the scale of recycling. In Portland, at least, there are recycle bins next to the trash can in most homes, buildings and public places; there are fleets of trucks and purpose-built facilities for processing recycled material. Kids are taught how and why to recycle. It’s a global industry. That all happened since the environmental movement of the 1970s.

What could we do to smooth, simplify, and scale the repair movement? What could movements like Right to Repair and Repair Cafe become if repair achieved the cultural and institutional buy-in that recycling enjoys? What if all the effort spent on recycling over the last fifty years had been equally distributed over the rest of the R’s, including reuse and repair?

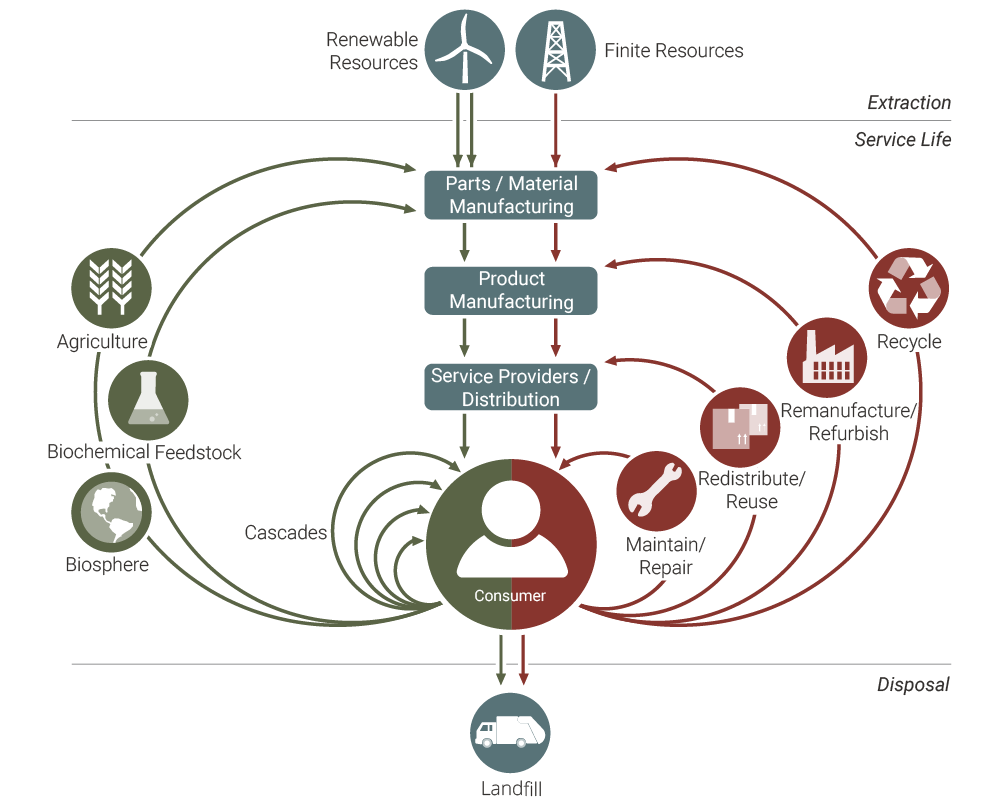

Perhaps the limitation is not that we couldn’t make repair widespread – after all, it has been before – but because we see all the R’s, whether 5 or 14, as equivalently “good.” A better way to look at this might be in the context of a circular economy, where resources and material goods are essentially a closed-loop system:

Mapping how resources flow in a circular economy. Adapted from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

Here the most efficient uses of materials are the shortest loops, requiring a minimum of reprocessing. Recycling is better than outright waste, but activities such as repair are preferred because they extend the actual service life of something, instead of just rerouting the raw material. In order to repair more and recycle less, we need to replace the 3-Rs triangle with something more nuanced and, frankly, complex than our current mental model of sustainability.

———

*As a candidate R word, Refuse has a confusing double-meaning: As a verb, to be unwilling to do something (such as use straws or plastic bags); as a noun, simply, trash.

PRF’s “Repair Reflections” series offers contemplations, ideas, and story to generate thought and conversation around repair-related concepts in our everyday lives.